This is going to be a long story.

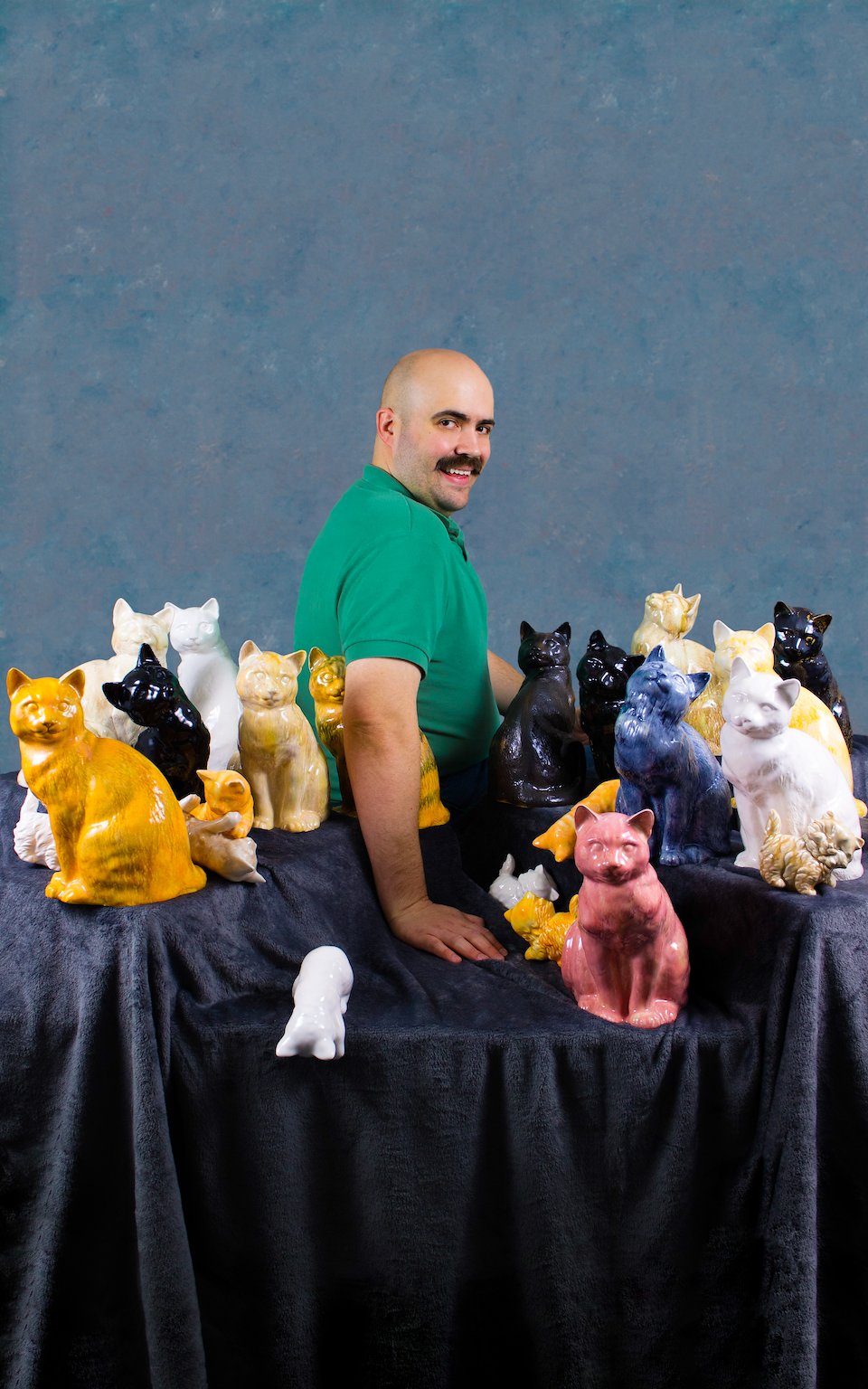

Homage

Archival pigment print, performance with ceramic objects (majolica on porcelain)

30 x 22 inches

2016

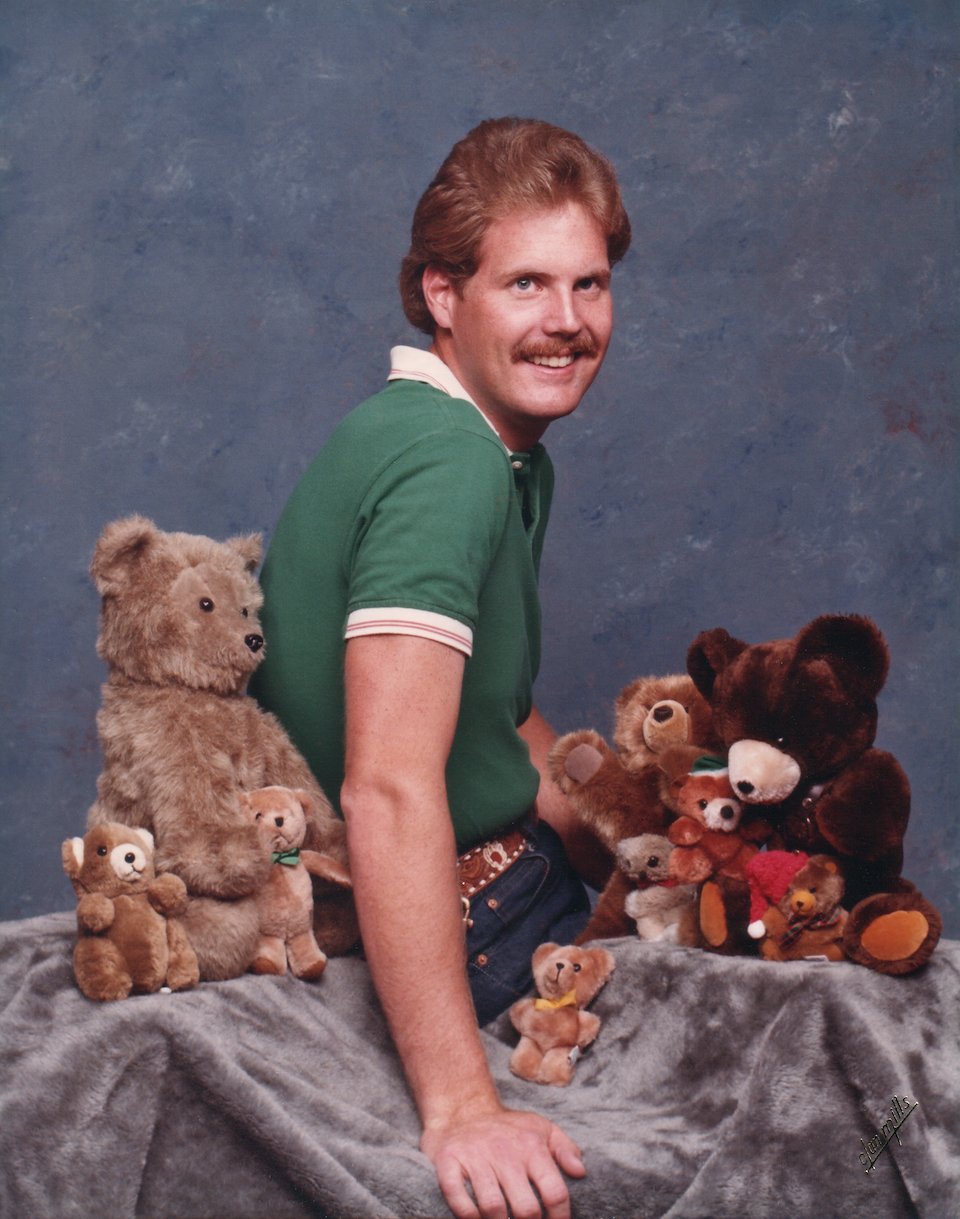

Gery’s Teddies

Olan Mills

1980s

From his husband Ben Aqua: “Back when Gery sported a magical dad stache and fluffy 70s disco hair (him and I obsessed over ELO), he booked a group portrait session at Olan Mills photo studio. He showed up alone, holding a bag. The photographer asked him where his group was, and he replied, "right here.” He then unloaded a bag full of teddy bears, strategically placing them in a delightful arrangement around himself. Genius."

First day of helping Gery at the 2013 Texas Clay Festival

Gery “Rocketskull” Henderson peacefully died in his home a week after I visited him in a sterile Austin cancer wing in 2016. Less than 30 days before, he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. He was happy and elated to see me, and my presence caused his hunger to finally come back after weeks of starving and being unable to keep any food down. During the visit, we shared a romantic knees-to-knees dinner of chicken verde enchiladas and a dessert of sugar-free vanilla ice cream with a sugar-free lime popsicle stuck in it (his version of diet key lime pie). I thought he was improving; his doctors thought he was as well. We even held a disco dance party in his bed to announce his improvement; I recorded it.

Afterwards, we held hands, I stared into his jaundiced face, and he confessed all his loves – for me, for life, for love, and for ceramics. He gripped my hand harder than ever before with his giant-sized hands and told me how hard life has been for him over the past 60 years, how he fought for his rights to be allowed to love whomever he wanted. “You deserve to be loved and to love,” he cried.

That was the last time I saw him. I left to celebrate my early birthday party with family, and then returned to New Bedford to start the semester. On the second night of being back, I couldn’t fall asleep until early morning. Something felt wrong in the world. I stared out at the moon and wondered. I texted Gery a series of rainbow hearts. Shortly after this, as his husband Ben would later write:

I held his hand and watched him as he took his final mortal breaths. I’ll never forget his last bizarre gasp of energy. He gently grabbed onto my shirt, somehow pulled himself forward, looked straight ahead into the backyard with his giant, gorgeous, bluebonnet blue eyes, and let nature take his consciousness eternally.

Sharing a booth with Gery at the 2013 San Antonio Clay Festival

He passed away that hot Sunday morning at the same time I finally could fall asleep.

Even though we were worlds apart, we were still connected.

Gery was the type of person I wanted to be. Passionate, caring, and patient; a queer man who was determined to live life to the fullest, to create art that he wanted to create. During moments of emotional crisis, he would be the friend I would call. He would have talked me off the proverbial cliff of quitting art and/or life. “You’re not a failure,” he would say in his raspy, luxuriously gay, El Paso drawl. “Lick your wounds – it’s okay to do that – but get up and fix it.” In these frequent sad moments when I wish he was here to both console and encourage, I remember something he once texted to Ben:

Stand up please

Close your eyes

Hug yourself hard

And pretend you’re hugging me

I do this often. It works every time. He’s here. My heart breaks and swells simultaneously. I can hold Gery’s work and feel his soul in every fired fingerprint. I put my faith in my hands and their touch, and I find hope in the futile ceramic process that acts like the perfect metaphor for life. Wonderful events happen that make you feel alive and want to dance down a hallway naked; sad, heartbreaking instances occur that make you want to hide in a hole and die like the failure that you are. I must remind myself that life is worth living. The ability to love is worth every shitty fucking moment.

Ceramics is real.

Until 2016, queer love was outlawed in Texas. Two years after Texas’ law on sodomy was overturned in 2005, I watched in horror as three-fourths of my state chose to discriminate against my type of love, making marriage only legal between a man and a woman (this would later be ruled unconstitutional in late 2014) (Ura). I remained in the closet until 2009, in part out of fear of public discrimination and private demonization. While other states started legalizing same-sex marriage around that time, many of my friends took vacations and were legally married elsewhere; the problem, though, was that Texas refused to acknowledge a binding contract of marriage from another state in order to preserve their homophobic dreams of heteronormative marriage traditions. This complicated the benefits married people would have: health insurance, wills, banking, tax benefits, etc. This was especially true for when a partner died and the widow/widower were legally a stranger – they had no rights over the partner’s remains.

We deserve dignity in our last, dying moments. We deserve to love abundantly and not in fear. The struggles of queer folk cannot be forgotten; queer love cannot be questioned or denied. If my art can be a vehicle to document its survival, then that is what my art will do. If my art can be a moment to grieve and let out the anger, then let it be so. My homage to Gery is the first piece done in my style that creates a tribute to a great love and weirdness that is gone. He was finally able to legally marry his partner Ben Aqua in 2015 at the Eye of the Dog Art Center (a mecca for ceramic artists in Texas).

In Homage, I recreated a scene from Gery’s past (circa the 80s) and made it about my present. In the original photo, Gery booked a group photo package at an Olan Mills studio and showed up with just himself and two trash bags. When the photographer asked where the rest of his group was, he said they were in his bag. He surrounded himself with a collection of teddy bears. He acknowledged his unique freakiness and pushed the boundaries. He was an artist before he knew he was an artist. He was the type of ceramic friend, brother, and lover I still need in my life.

As Texas (and the Trump administration) continues to discriminate against my queer family, I am ready for war. I don’t seek a war for acceptance, per se; rather, I seek a war in the name of love. Love knows no boundaries. You may think I’m a disgusting monster for my sexuality. But know that what disgusts you doesn’t deserve your hatred, it deserves your admiration. We are different beasts, different tribes, and we can respect each other with love and compassion.

I wouldn’t exist without you, and if I must be a warrior for the next generation, then let it be. Family, I want you to see that through my notion of visible freedom, you are not alone in a vacuum of sorrow. I see you. You exist. You will not be ignored. Your life, your love matters. Now, stand up, please. Close your eyes. Hug yourself hard. And pretend, in this moment my love, that you are hugging me. I am real and so are you. No one can deny this.

As Gery would say, “FEEL EVERYTHING.”

The original Cult of Gery Cameo Necklace

Addendum:

During that summer after his diagnosis, there was a Facebook support group that emerged to support Gery. It was a way to communicate with each other rather than text Ben non-stop. I made a rough cameo necklace as part as an art demo and I started to wear it everyday. I posted the image to the group, and it blew up. Everyone wanted one, so I uploaded a better drawing and a sticker sheet and let it go. The following are some of the examples of the art people made during this outpouring of collective love while he was in the hospital, and then once again during his memorial party.

Updated Cameo Drawing

Gery Sticker Sheet

Cameo by Ben Aqua

by Kelli Cotner

by Sierra Ho (photo Ben Aqua)

Gery Tiles by Bridget Hauser

Tattoos by Jennifer Quarles (photo Cody Clinton)

Gery Tiles by JoLea Arcidiacono

Gery Tattoos (photo Tawni Bates)

Gery Hanky (photo Ben Aqua)